The Floating World

The woodblocks depicting "the floating world" of Japan, created between the 17th and 19th centuries, have become synonymous with the country itself and an iconic visual of Japanese arts and culture of the time.

Ukiyo-e, the floating world, takes its name from the Buddhist term, ukiyo, which expresses the notion of the fleeting nature of life. While the concept generally centers around the negative side of impermanence, during the Edo period, this notion was celebrated instead of mourned. The Japanese character, or kanji, "to float," was substituted for "transitory," giving a new, optimistic meaning toward the celebration of life.

Woodblock printing originated in China during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) and was most commonly used to reproduce texts for the masses. Even though typesetting (movable type) was eventually the more "tech-savvy" method for producing texts, the relief process remained a widespread method that Japanese artisans employed to make images.

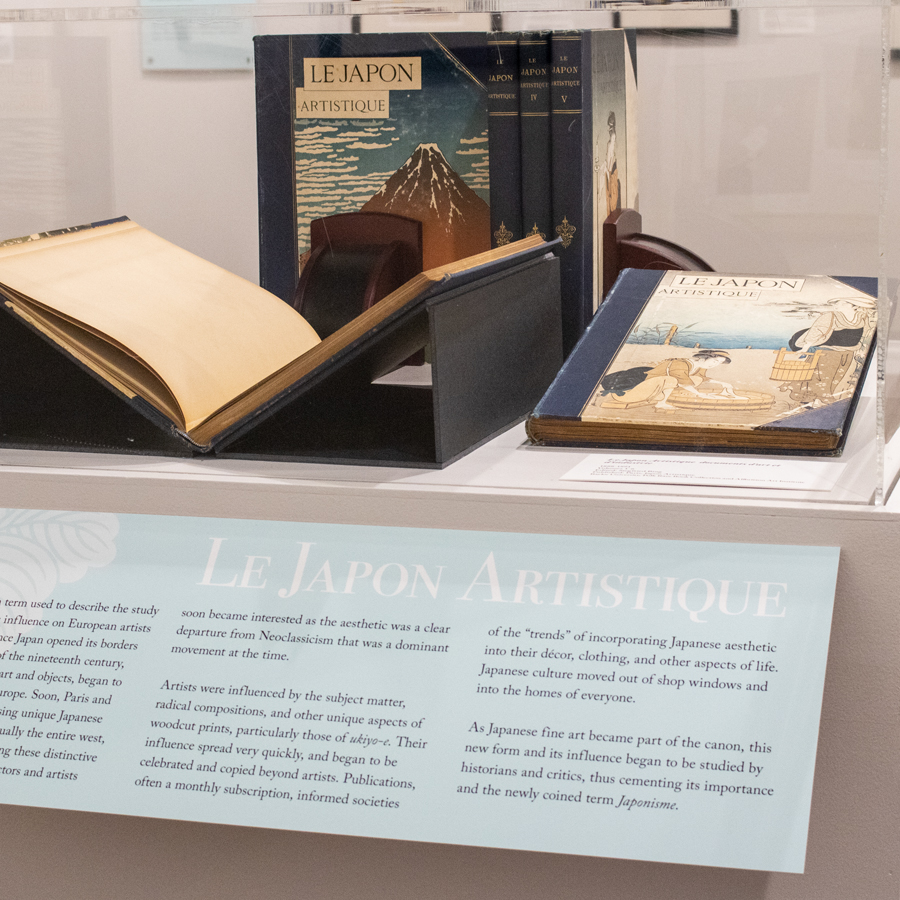

Le Japon Artistique

Japonisme is a French term used to describe the study of Japanese art and its influence on European artists and art movements. Once Japan opened its borders to the world at the end of the nineteenth century, its products, namely fine art and objects, began to be exported throughout Europe. Soon, Paris and London's shops were showcasing unique Japanese pieces. Europeans and the entire West became obsessed with collecting these distinctive new items and artworks. Collectors and artists soon became interested as the aesthetic was a clear departure from Neoclassicism, a dominant movement at the time.

Artists were influenced by the subject matter, radical compositions, and other unique aspects of woodcut prints, particularly those of ukiyo-e. Their influence spread quickly and began to be celebrated and copied beyond artists. Publications, often a monthly subscription, informed societies of the "trends" of incorporating Japanese aesthetics into their décor, clothing, and other aspects of life. As a result, Japanese culture moved out of shop windows and into the homes of everyone.

As Japanese fine art became part of the canon, this new form and its influence began to be studied by historians and critics, thus cementing its importance and the newly coined term Japonisme.

The Kabuki Stage

The captivating stories and charismatic stars of the kabuki theatre were popular subjects for Japanese printmakers. Kabuki began in 1603 when a troupe of female dances led by a miko shaman, Izumo no Okuni, performed in a riverbed in Kyoto. The dance dramas became very popular with all segments of society, and multiple troupes formed in Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto. However, the shogunate did not approve of the association between female Kabuki and prostitution, so in 1629 women were banned from performing, and the troupes became all male. Male actors took on female roles and became specialists known as onnagata.

Kabuki grew in popularity, reaching its pinnacle from 1673-1842. Kabuki actors became the celebrities of the floating world, appearing in prints and magazines with devoted fan followings.

As a theatrical form, Kabuki emphasizes actor and their performance rather than prose. Through dance, elaborate costumes, stage, and highly stylized movement, Kabuki creates a very specific drama and look. Actors use this form to showcase their talents and have kept the traditions first created by Kabuki actors centuries ago.

Women

While women have long occupied a central theme in the art world, they received special attention in Japanese art, particularly during the Edo period. Japanese women of the pleasure quarters, prostitutes(yūjo) and geisha, were, in their own right, celebrities, which made them popular subjects for ukiyo-e printmakers. An entire subgenre of ukiyo-e, known as bijin-ga (paintings of beautiful people), is devoted to them.

Geisha, who started to emerge in the 1750s, were entertainers but are often mistaken as prostitutes, who had existed much longer. Geisha were expected to be well-read, cultured, and elegant but did not usually offer sexual services.

Unlike traditional prostitutes, oiran were entertainers and prostitutes and were considered to be of a much higher "rank." To become an oiran and, thus, command a higher price for one's services, a yūjo had to learn traditional Japanese arts such as ikebana (flower arranging) and tea ceremony, as well as master a variety of musical instruments.

The 53 Stations of Tōkaidō Road – A Journey in Images

The Tōkaidō was an imperial road set up by the ruling shogunate as a path for citizens to travel to bring offerings to the current ruler during the Edo Period. The road connected Edo (modern day Tokyo) to the emperor’s palace in Kyoto. 53 stops, or stations, were created along the road as stopping points for weary travelers. Before Hiroshige created his now-famous 53 Stations of Tōkaidō Road in 1833, this road was already a very popular scenic route. Travelers could see temples and shrines, stay at inns, and shop. Hiroshige’s images of the Tōkaidō further boosted its popularity, fundamentally shifting it from a functional road of access, to that of fame making it a true tourist attraction.

This series of prints has been recreated several times throughout the Edo Period. Several editions and series illustrate different views of each station, while some are smaller in number, or focus on specific aspects of the road.