The Art of the Landscape

Connecting to the Landscape

The general concept of the landscape in art has existed for as long as visual art has been made. The Renaissance ushered in an era of thought about the natural world, leading artists to consider the land itself as a possible subject. As a genre of art, landscape painting formally emerged in the Netherlands during the 1500s. As the population grew more Protestant, the middle class began searching for secular artwork to adorn their homes’ walls, and landscapes became popular.

However, France and Italy did not initially value the landscape as a subject and instead preferred history painting, portraiture, and lifestyle painting as dominant subjects of the time. As a result, landscape painting did not take hold in the two countries until the 17th century. Even then, it was primarily used as a mere backdrop for historical and biblical scenes.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries gave rise to the Classical landscape throughout western Europe. Artists attempted to create the perfect space, harkening back to the classical beauty of Greek sculpture and antiquities. In 1800, Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes published a book centered on the ideal of the “historic landscape,” which he said had to portray actual, physical nature. This book represents the beginning of art academies accepting the landscape as a high art form.

In the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution dramatically altered the landscape, both metaphorically and physically. As urban centers formed and expanded, painters began moving away from rural areas to paint cities or more accessible areas outside their doors. At the same time, photography began to gain recognition as a fine art medium and would change the concept of the landscape yet again. Cityscapes and urban centers became subjects sought by photographers. The landscape began to change again as the 20th century led to an exponential diversity of movements and techniques. Abstract artists became interested in creating their own version of the landscape. They were less interested in representing the visual space as it existed and began to focus on other expressions and experiences related to the landscape.

The landscape continues to serve as a way artists connect to the places people experience and how humans interact with and affect those spaces. The landscape is captured in all visual media across the globe and understood by us all.

Vastness Captured on Canvas

One hallmark of a good landscape is the artist’s ability to create three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. When looking at a landscape, the viewer will notice many “tricks” employed to produce the illusion of space and depth.

Several unique design techniques can help a viewer to “see into the distance” of a landscape. Objects can be arranged in an overlapping manner that partially occludes those in the background, thus creating the illusion that one object exists in front of the other. The use of attached shadows also became a widely used tool in the Renaissance to create a sense of depth on the picture plane. The physical placement on the two-dimensional plane can also give a viewer clues. Objects placed lower on the physical surface appear closer, while those near the top of the surface are considered farther away from the viewer. Distance from the viewer is also implied through the use of scale. Larger objects appear closer, and we perceive those rendered smaller as further away.

A more scientific method, known as linear perspective, combines the systematic use of lines that converge to a vanishing point to create the perception of depth on a two-dimensional surface. The concept of linear perspective is thought to have originated in the early 15th century by Italian engineer Filippo Brunelleschi. He created a system that uses vanishing points to place objects into a picture plane. The system can be set up using one vanishing point or two. As objects get closer to the vanishing point(s), they shrink in size. The vanishing point always meets the horizon line.

Atmospheric perspective is another form of perspective that artists rely on to create depth. The concept is simple; the atmosphere itself becomes an obstacle to our vision. The further an object is, the less detail we can see. Edges blur, colors appear dull, and detail dissipates. Objects meant to be further away in the picture plane are created with less detail, less color, and less precision.

These tools help an artist transform a flat surface into a seemingly three-dimensional space. These discoveries in representing perspective and producing an illusion of depth changed how artists create works and how we interpret them as viewers.

Selected Works

Peter Lanz Hohnstedt, Untitled Landscape, ca. 1925, Oil on canvas

Maria Dumbrava, Mirific, 1980, Monotype

Earnest William Christmas, Mountain Lanscape, ca. 1900, Oil on canvas

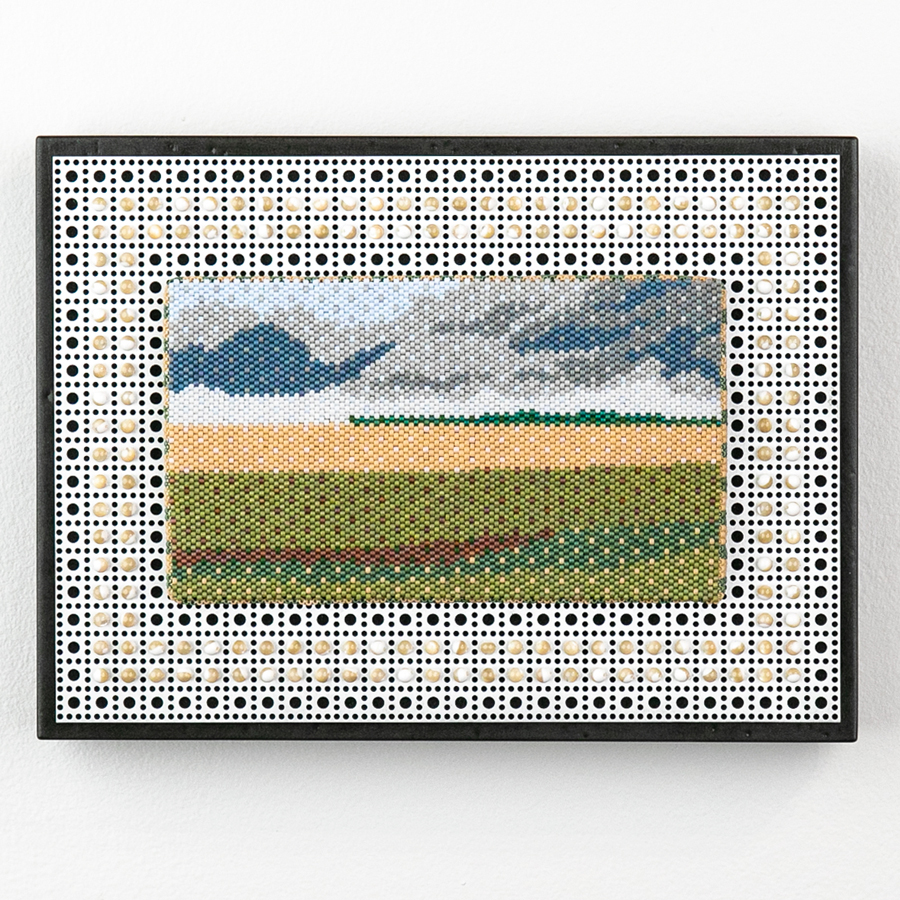

Leah Force, On the way to a Dream, 2011, Delica glass beads, mixed media

Aubrey Dale Greer, The Bridge, Late 20th c., Oil on canvas

Porfirio Salinas, Cactus of Texas, ca. 1950, Oil on canvas

Dan Wingren, Late Wilderness, 1957, Oil on canvas

Aubrey Dale Greer, Untitled Landscape, Late 20th c., Oil on canvas

Gibbs Milliken, Dormant Earth, 1966, Acrylic on board